From geology and more specifically to meteorites, there is a tactile connection to space and the universe that’s tangible even with one’s feet planted on Earth -- or to be more exact, in the Rankin Science Building. In a dusty room, covered with colorful geological maps, signs of research abounded with samples of rocks and slides strewn about the room’s surfaces. Anthony Love, research operations manager for the Department of Geology at Appalachian State University, shared two artifacts -- a piece of the moon and a piece of Mars -- while talking so excitedly about science that gravity might have been the only thing keeping him in his seat.

Several years ago Love was approached by science enthusiast Don Cline, a member of the College of Arts and Sciences Advancement Council and a supporter of many campus and state science development initiatives. Cline asked Love about his passion, which is classifying and vetting unknown meteorite materials. Love described his work as defining how these materials taste, classifying their composition and sharing the markers of their story.

“The rock’s chemistry can tell us where it came from and how it formed,” said Love. “We may not have the tools here on campus to study Isotope systems that would show the age of these materials, but we do have the instruments to study their origin and classification.”

Geology is the study of the origin and evolution of our planet, and meteoritics is the planetary science that studies the origin and evolution of our solar system. A meteor, also known as a shooting star, occurs when a piece of an asteroid or a planetary body enters the atmosphere. When it lands on Earth, it’s called a meteorite.

Geology is the study of the origin and evolution of our planet, and meteoritics is the planetary science that studies the origin and evolution of our solar system. A meteor, also known as a shooting star, occurs when a piece of an asteroid or a planetary body enters the atmosphere. When it lands on Earth, it’s called a meteorite.

“A meteor loses about three-fourths of its mass during atmospheric entry, so the rocks that make it to earth as meteorites have to be a certain size to survive their passage through our atmosphere,” explained Love. “To say all that is one thing, but to hold, to learn and think about that object in the palm of your hand is another.”

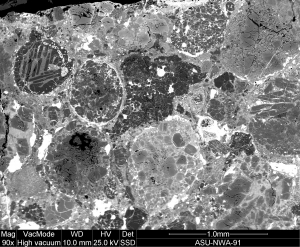

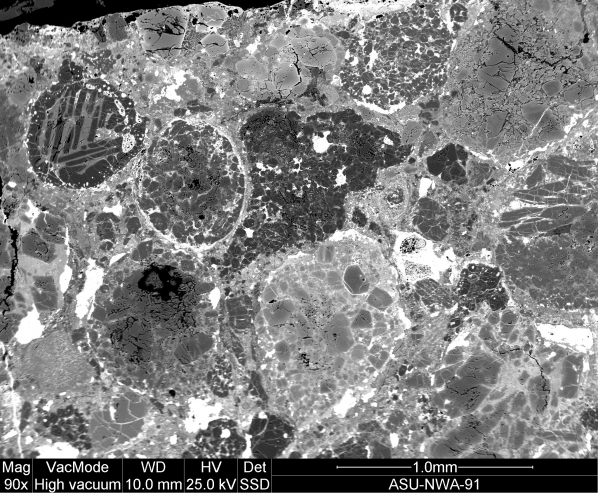

Love’s research involves taking thin sections of rock to evaluate their internal texture and the minerals in their makeup. The main differences in distinguishing a meteorite from any rock is magnetism and density. The specimen Love shared, hardly bigger than a quarter, was a piece of the moon’s surface.

“That piece came from the crater formations we can see in the moon,” said Love. “Those craters occurred from impact to the moon’s surface and broke a portion of the subsurface away and that is what you hold in your hand.”

Love was not always this passionate about meteorites in his geological studies. His interest in meteorites did not come about until 2006. His work now is summed up as the closest tangible opportunity to connect with space since that infatuation. And since then, opportunities have been presented with great encouragement and support from his fellow faculty and resources in the community. With no further degree studies, these opportunities have come to him through great dedication, support and research. As he explains, his work isn’t necessarily categorized as science, but without classification of geological materials, scientists cannot do their research. For Love, it is the excitement of working with these materials and making these new distinctions that bring him to work every day.

###